Home, Sweet Home

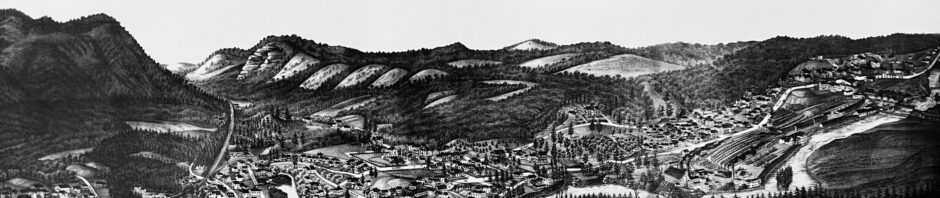

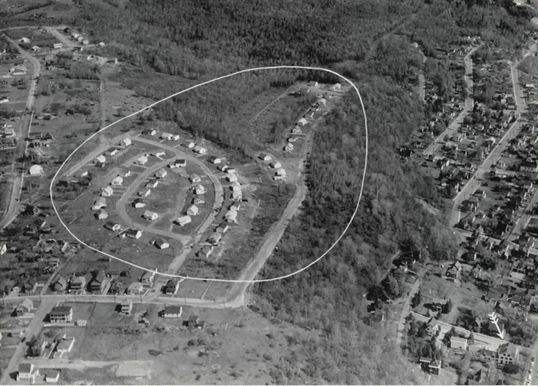

Subdivisions, and the neighborhoods that they created, continued after Berlin’s heydays into the post-war years. Highland Park, located west of Ramsey Hill Park, was developed by the Brown Company in the mid-1950s as “low-cost modern housing” primarily for Brown Company employees. The idea of a new neighborhood was conceived of in 1953, when Philip “Babe” Smyth of Local 75 of the Pulp-Sulphite Workers Union and Brown Company Vice President John Jordan joined forces. Laurence F. Whittemore, Brown Company President also played a role in the project. (The three men are commemorated in the community’s street names.)

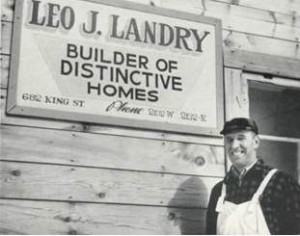

A 13-acre site (with later additions) on Ramsey Hill belonging to the company was selected for the project. Brown Company acted as the developer, hiring Massachusetts landscape architect and planner Americo Nemiccolo (1904-1966) to lay out the streets and building sites. Leo Landry was the general contractor for the houses.

Each Man’s Home His Castle

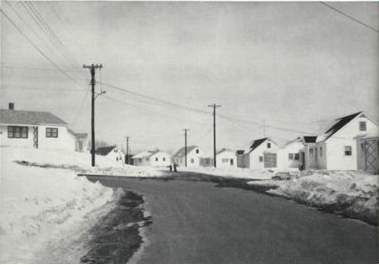

The first houses were built on Jordan and Smyth Avenues in 1954 (12 houses), 1955 (17 houses) and 1956 (10 houses). Running out of space, the subdivision expanded to Highland Park Avenue and Whittemore Avenue. In the process, Highland Park Avenue was extended through to 12th Street to connect with the Halvorson Terrace development. This provided an alternative access to the west portion of the city, avoiding the steep Hillside Avenue. By 1958 there were 53 homes in the area.

Highland Park was one of a myriad similar projects located throughout the country (including such well-known larger examples as Levittown) which sought to alleviate critical post-war housing shortages (and sky-rocketing prices) of single-family houses. The Highland Park neighborhood, like many projects of the era, was made possible in part by loan insurance from the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). Established during the Depression, the FHA insured the mortgages of individuals who might otherwise have difficulty obtaining mortgages at reasonable rates. In the case of Highland Park, loans for the houses were provided by the New Hampshire Savings Bank, in Concord with the Federal Housing Administration backing the loans. The FHA established certain national minimum standards for home construction, including such items as house size, setbacks and location, which developments had to meet. These standardized requirements played an important role in standardizing both subdivision design and housing design throughout the country. FHA-insured loans which had lower interest rates, down payments and monthly payments, weren’t generally available in older urban neighborhoods that did not meet the FHA requirements. This had the effect of encouraging new standardized suburban development throughout the country.

Mrs. Russell Kinney tried to persuade little Sandy to look at the camera, but she was still sleepy and a bit shy after her nap.

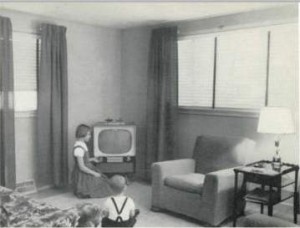

For Berlin, where three-story “Blocks” housing multiple families continued to be built into the early 1930s, this shift to smaller single family houses was a sea-change. In Highland Park, the standardized designs came in two basic models. The “standard” house was a 4-room, 24’ x 32’cape, priced at $8,950. It included a living room, two bedrooms, a bathroom, a modern kitchen and full cellar. The attic was unfinished, but could be converted into two bedrooms and a bath in the future. The slightly larger (24’ x 36 ½’) $9,950 model was a ranch with five rooms and three bedrooms. The minimum down payment was $450 on the smaller house. The interiors of the homes were described as being finished “in the most modern designs.” Floors were clear red oak, with Chinese mahogany doors and Arkansas pine woodwork. The houses’ “modern” heating system as well as their “completely equipped” baths and kitchens were touted, as was their ample closet/storage space and natural light.

Examples of the Highland Ranch and Cape Models today:

|

|

[See articles on the neighborhood in Brown Company Bulletins March 1955 and May/June 1958]

Follow

Follow